There are four reasons your plane wants to veer left when you are taking off. They’re called left-turning tendencies. The reasons that your airplane wants to turn left are:

- Torque Effect (reaction from engine and propeller)

- Spiraling Slipstream (Corkscrewing effect of the slipstream from the propeller)

- P-factor (Asymmetric loading of the Propeller Disc)

- Precession (Gyroscopic action of the propeller)

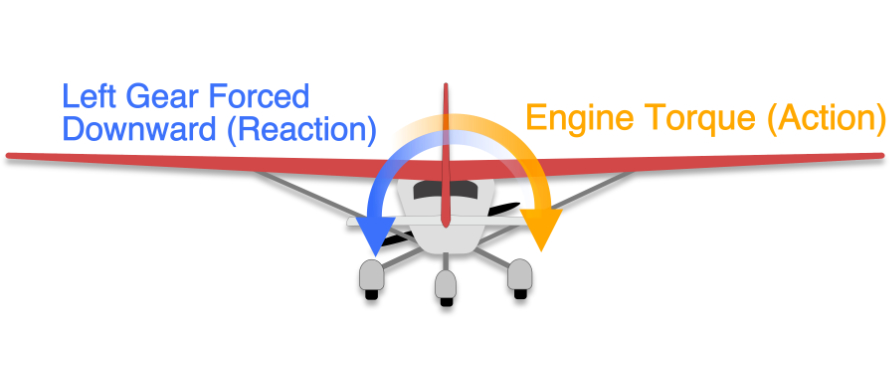

Torque

- Torque is a measure of the force that can cause an object to rotate about an axis.

- According to Sir Isaac Newton’s Third Law… “For every action, there is an equal and opposite reaction.”

- The propeller on a single engine airplane is driven clockwise (from the point of view of the pilot) directly by the crankshaft of the engine .

- When the propeller turns in the clockwise direction, the airplane will want to roll in the opposite, anti clockwise direction.

- During the takeoff roll the engine is developing maximum power.

- The left roll forces the left side of the aircraft downward toward the runway and in turn causes the left hand side tire to have more friction with the ground than the right tire, thus turning the aircraft to turn left.

- Torque effects the airplane in ALL phases of the flight

- The way to counter spiraling slipstream is to use right rudder.

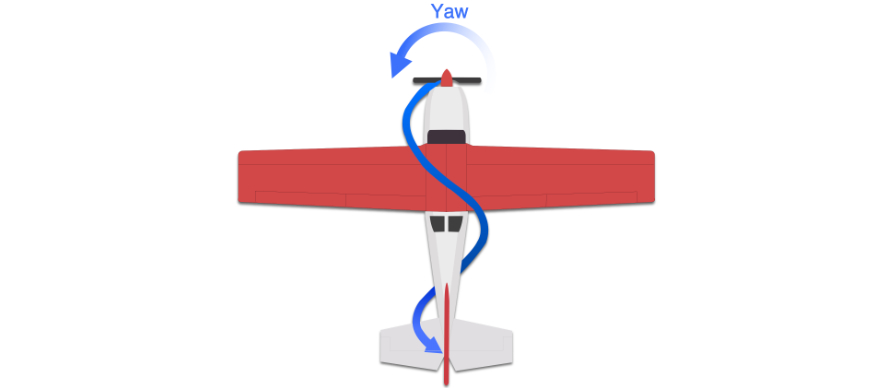

Spiralling Slipstream

- During takeoff, (High Propeller Power, Low Airspeed) the air accelerated behind the propeller, known as the ‘slipstream’, follows a corkscrew pattern.

- Wind blown aft by the propeller spirals around the aircraft, then strikes the left side of the vertical stabilizer.

- This causes the tail to swing right and the nose to yaw left around the vertical axis.

- Spiraling slipstream has its greatest effect upon the airplane when your propeller is moving fast and your plane is moving slow. Takeoff is a great example of this scenario.

- An airplane in a climb compresses the spiral causing it to be felt to a greater degree.

- As forward speed increases the spiral elongates and becomes less effective.

- The way to counter spiraling slipstream is to use right rudder.

P-Factor

- P-factor describes the uneven loading of a propeller (or the asymmetric loading of the propeller), which develops at anytime the airplane has a greater angle of attack than 0°

- The descending blade of the propeller takes a bigger bite of air than the ascending blade in the climb (also has a greater forward velocity).

- It therefore creates more thrust on the right side of the propeller than the left side, causing the airplane to turn left.

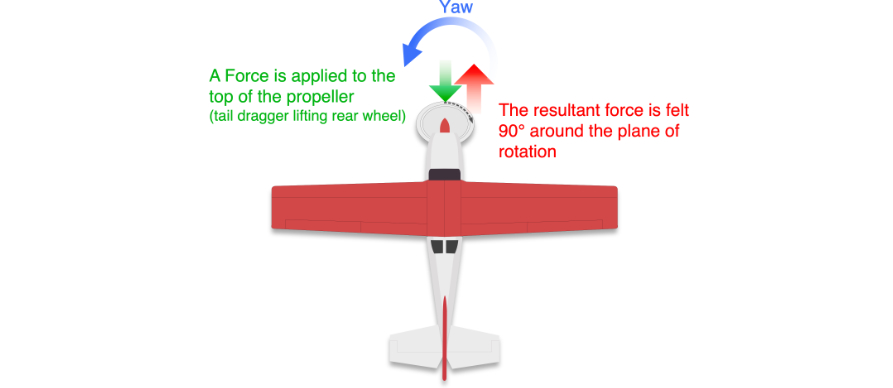

Gyroscopic Precession

- A spinning propeller is essentially a gyroscope (a spinning disc).

- That means a spinning propeller takes on the two properties of a gyroscope

- Rigidity in space

- Precession.

- For this lesson we are only going to explain the precession part.

- Precession happens when you apply force to a spinning disc. (In the case of an airplane you will change the pitch of the airplane.

- When you apply a force to part of the disc, and the effect of that force (the resultant force) is felt 90° in the direction of rotation of the disc.

- This, for the most part, only applies to tailwheel airplanes when they lift their tail off the runway during takeoff.

- As the tail comes up, a force is applied to the top of the propeller. And since the propeller is spinning clockwise, that force is felt 90 degrees to the right.

- That forward moving force, on the right side of the propeller, creates a yawing motion to the left.

Counteracting Left-Turning Tendencies

- Right Rudder Input

- Takeoff and Climb: Apply right rudder pressure during takeoff and initial climb phases to counteract left yaw. The amount of right rudder needed will depend on power settings, airspeed, and angle of attack.

- Cruise: Use small adjustments as needed to maintain coordinated flight.

- Rudder Trim

- Use rudder trim (if available) to relieve the need for continuous rudder pressure. This helps maintain a consistent heading without constant rudder input from the pilot.

- Aileron Input

- While primary correction should be with the rudder, slight right aileron input can help counteract any rolling tendency. Be careful to avoid over-correcting, which can lead to uncoordinated flight.

- Power Management

- Apply power smoothly to avoid abrupt changes that could exacerbate left-turning tendencies.

- Be mindful of power settings, as higher power settings often require more right rudder input.

- Pitch Management

- Manage the pitch attitude carefully, especially during climb. A high angle of attack increases P-factor and gyroscopic precession effects, necessitating more right rudder.

- Coordinated Flight

- Regularly check the turn coordinator or slip/skid indicator to ensure the aircraft is flying in coordinated flight. Use the “step on the ball” method, applying rudder pressure in the direction of the ball to center it.

- Practice and Familiarity

- Spend time practicing coordinated flight and rudder use during different phases of flight and power settings. Familiarity with your specific aircraft’s behavior will make it easier to anticipate and counteract these tendencies.

Practical Tips

- During Takeoff Roll: Gradually increase right rudder pressure as you apply full power. Be prepared for the need to increase pressure as the tail lifts (in tailwheel aircraft) or as you gain speed.

- Climb Out: Maintain steady right rudder input during the initial climb. Adjust as necessary to keep the aircraft coordinated.

- Level Flight: Use rudder trim if available to maintain straight flight without constant rudder pressure.

- Descending and Power Reduction: Be aware that reducing power may require a decrease in right rudder input to maintain coordination.

By understanding the causes and practicing these techniques, you can effectively counteract the left-turning tendencies in single propeller aircraft, ensuring safer and more coordinated flight.